Will Self At CERN: An old argument in a new form

/Aerial View of the CERN, Maximilien Brice (CERN)

I have friends whose idea of heaven – and mine of hell – is Power Ballad Night at the Electric Ballroom. They go, I don’t, and we are all happy. So I was puzzled by the five-part BBC radio programme Self orbits CERN (podcasts here), in which author Will Self walks the 50km route of the Large Hadron Collider that lies beneath the French-Swiss border. He tells us that he’s been persuaded by Akram Khan (Professor of Experimental Particle Physics, and Self’s colleague at Brunel University) to visit CERN and ‘feel the wonder’, and essentially he spends 75 minutes telling us how much he hates the trip.

Nothing repels like zealotry, especially if you are already antipathetic, and Self, who seems to have arrived with a rucksack of negativity, is resolutely unimpressed by his enthusiastic guides, or any part of the operation. He feels no ‘wonder’ at seeing huge machines, and since this is about the best that CERN can offer, he understandably experiences no Damascene conversion. Instead he snipes at the people sent to meet him, asking why they’re doing it for, and being disappointed by their responses. When they say it’s to understand the world, and also to advance technology, or they explain that it’s a monument to human cooperation, he is unconvinced; this is just PR he tells the listener. “I’m getting fed up to the back teeth with these CERN guys; I don’t want to hear one more time how they’re a saintly brotherhood dedicated to a higher cause.”

And of course it is PR – he is after all talking to CERN PR representatives, and that’s their job, and the scientists are also being amateur PR people, because they believe that keeping this monumental project going requires that. Having complained about the saintly brotherhood, he then, a little contradictorily, finds it unacceptable that for some it might ‘just be a job’ – it should be some sort of calling, “a Promethean quest to wrest fire from the Gods!” – and is dismissive of the idea that they might have been intimidated by him and his language. But the reason he’s unconvinced goes deeper: “behind it lies a core belief “, he says, “and in the case of the scientists here at CERN, it’s a belief in progress, and the question is, what is that progress for, because progress in and of itself doesn’t have any moral value, in my view”.

Whenever he meets someone, he asks them to explain what they do, and then gets angry that they lose him almost immediately. In Episode Four, Akram Khan sits down with him and (at last) asks what Self himself actually does understand about the atom; and from some sort of shared perspective, they have a conversation that, albeit briefly, brings a sense of connection. “You’ve done curly little spirals there to show gluons, why’ve you drawn them as curly little pigtaily things?’ -“Er, because they look good?”. But the impression I got throughout is that Self’s cries of ‘I don’t understand’ have a subtext of ‘and I don’t really want to’. Both sides were interested in being understood, but not particularly in understanding the other.

Certainly there’s a lesson for science communicators about meeting people ‘where they are’, and the attempt described above only partly does that. “Out beyond ideas of wrongdoing and rightdoing, there is a field. I will meet you there”, wrote Rumi, and it seemed to me Self’s field was not understanding the structure of an atom, but more questions of ‘why should I care?’, ‘why should I believe you?’, ‘what is your philosophical viewpoint’, ‘what are the real social and political issues here?’, and – like all good detectives – ‘who benefits?’.

In between his unsatisfactory meetings, Self complains about his prostate, the accommodation, and the rain, though finding this last appropriate in that he’d just told a CERN worker that the Greek philosopher Thales thought that the world was all liquid.

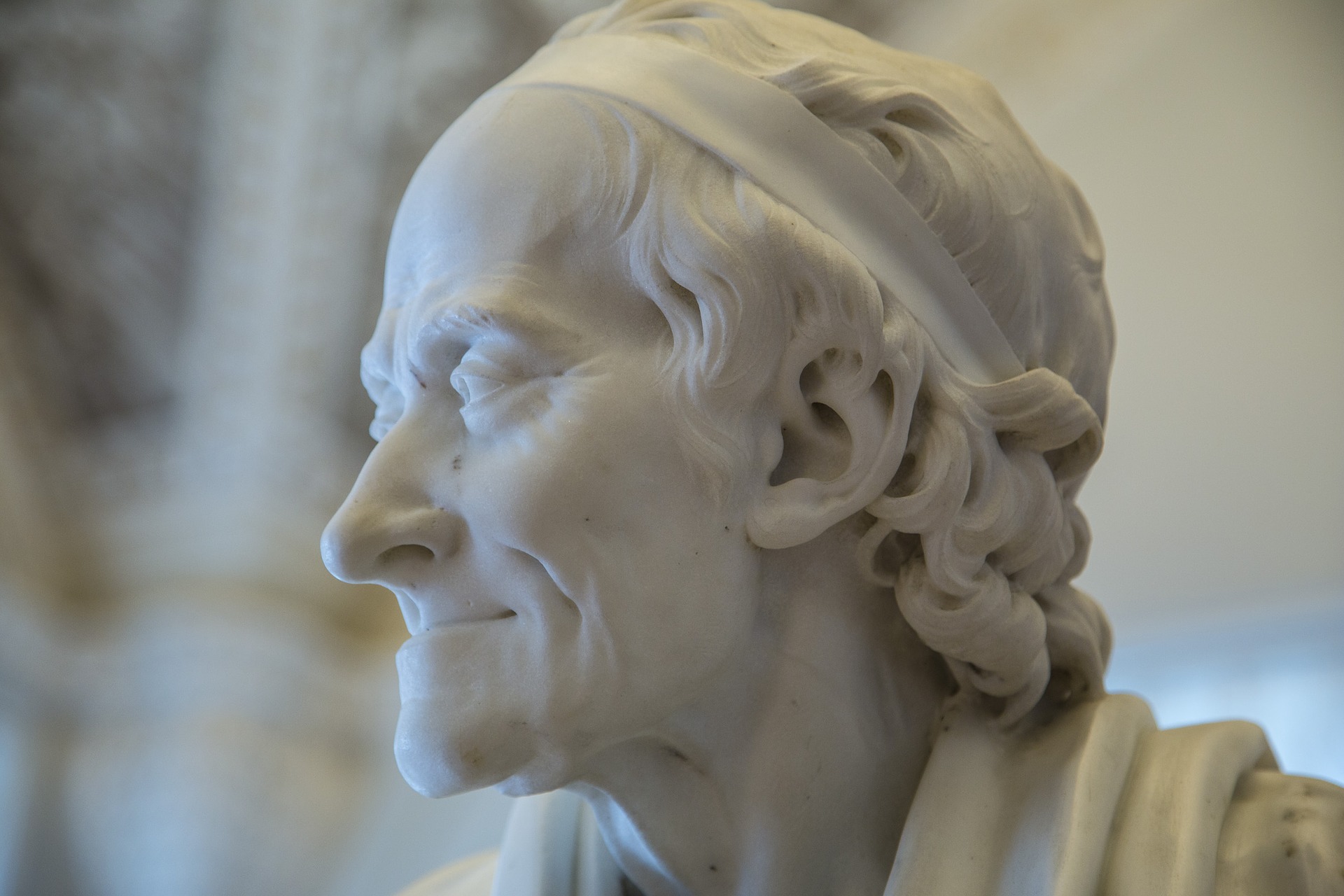

Statue of Voltaire, Image by korpiri

The journey ends at Voltaire‘s chateau, which seems fitting, as Voltaire, impressed by English science, had brought Newton’s writings to France. But Self leaves Geneva as he started, seeing himself more as Voltaire’s opponent Jean-Jacques Rousseau, who wrote in his Discourse on the Arts and Sciences, “If our sciences are futile in the objects they propose, they are no less dangerous in the effects they produce”, and challenges “Tell me then, illustrious philosophers, of whom we learn the ratios in which attraction acts in vacuo; ….; and what insects reproduce in an extraordinary manner. Answer me, I say, you from whom we receive all this sublime information, whether we should have been less numerous, worse governed, less formidable, less flourishing, or more perverse, supposing you had taught us none of all these fine things”. It seems that the battle between Enlightenment and Romantic values is still being played out.

So perhaps some things are never meant to be; just as I never expect to love an evening of Jennifer Rush, I can’t see Will Self ever getting very excited by gluons