Alice Anderson: Memory Movement Memory Objects

/Zoe Middleton (reproduced with permission)

First things first, in case you read no further: go and see Alice Anderson’s exhibition, Memory Movement Memory Objects, at Wellcome Collection. I found parts of it extraordinary, that I have returned to repeatedly. The curation, integrating strong design and careful lighting with the artist’s works, has produced effects that are aesthetically powerful and thought-provoking.

But I’ve struggled to write this piece, to express what it meant for me in the context of what it appeared to mean for the artist, and why it was in this venue. And I’ve continued to wrestle, intrigued that it has stayed with me powerfully, but is so hard to pin down.

The first room you enter in the show has the air of an antechamber. The surfaces are black, the light is dim, and there’s a desk with attendant. On the left there is activity with people in black overalls engaged in creating more work.

I pass through, turn the corner, and enter – if that was the antechamber – the temple or the tomb. Here, a myriad of objects are frozen, mummified exquisitely in webs of burnished copper wire, and they glow in pools of light within the blackness. They are arranged almost liturgically, displayed on an avenue of pillars that form a path to a shimmering staircase, one that leads perhaps to another world. And it’s quite, quite sublime.

The objects on the stands, and arrayed along each wall, are recognizably from this world: for example, vases, spectacles, a flat-screen TV. The Tutankhamun aesthetic is impossible to avoid, and all these seem prepared for use in the afterlife.

There is something about the colour and sheen of untarnished copper. For me it brings back memories of painting the keels of Airfix model ships with Humbrol enamel, marvelling at its richness. It has a depth that other metals lack.

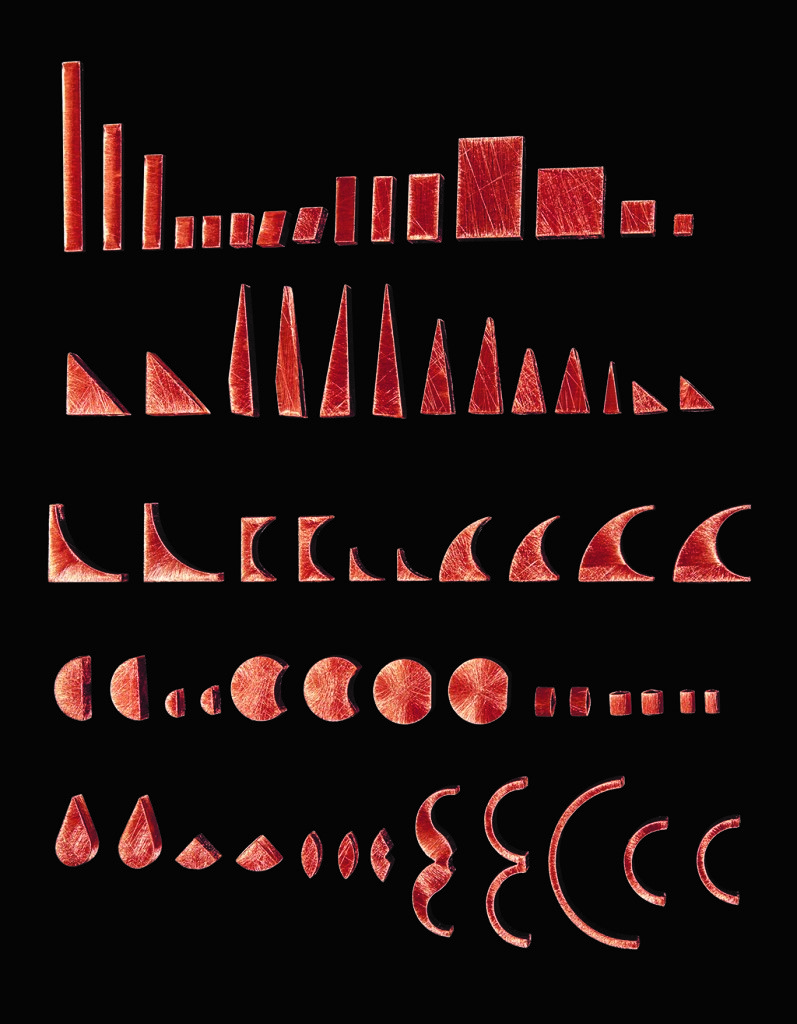

I move on through the rest of the exhibition, and other rooms hold powerful installations. In one, ropes – thick like the ones that used to hang in school gyms – loop around each other, filling the space like a fantastic three-dimensional doodle that you can climb inside. There is a circle of tall copper-encased panels like standing stones, again invoking a ceremonial or sacramental space. And there is an iridescent ring of copper mounted on the wall. I could spend a lot of time with all of these, or with the wall displays of collections of small objects – coins or geometric shapes. Other rooms, this time bright white, hold objects that are recombined, or have started to deform, and the effect is very different. Adjacent objects diminish rather than enhance each other, and I don’t stay.

The title of the show demonstrates that Anderson’s concerns are about memory, and perhaps this is the reason it within Wellcome Collection at all. I can see how someone who starts with that concern can end up here, but I’m not relating to it.

So I return the next day, and this time I act as an assistant, helping mummify objects in the anteroom. I find that the ‘wire’ is filament-thin, and that the process is not so simple. I’m taking over a partially finished mobile phone, and, as I sit in my black coat, find that to cover it in any depth seems to take forever, and that some parts of the object – the curves, the ends – are extraordinarily hard to deal with.

On the third day, I work on the main object in the room, a 1968 Ford Mustang, and the process is different again, being physically demanding as I walk and bend and stretch. For some of the time I’m sharing with five other helpers, and we perform an elaborate freeform Maypole dance.

Walking round and round the car brings to mind Richard Long, for whom walking was an integral part of his practice. I also become lost in other thoughts that come and go, about what I’m doing, where a particular thread is going; a rhythm sets in, then changes; other people duck past me seamlessly, or are momentary irritations that break the spell. I gather that the process for Anderson is about paying attention to the objects, preserving them as memories in some way, but for me it is becomes about the time spent walking or winding, and the resulting transformed object feels a mere byproduct.

Taking part in the process does change how I see the other objects in the exhibition; I start to marvel at the time spent, and the ingenuity needed to completely encase objects. But I still don’t connect with this as memory, except where the presentation within the space combines to give it meaning.

Then I contemplate that the point of writing a review is as a way to reflect on what I’ve experienced. I use a thread of words, woven around my memories of the event and the ideas they evoke. Out of that process I hope to find some resolution, a moment of understanding, that might not be possible without stopping my thoughts on paper.

And perhaps that is the connection I’ve been looking for? Perhaps this is all about the perception of stability and continuity, a trick that our mind plays both about the world around us, and also about itself. We see our flow of thoughts as coherent and enduring, as opposed to disconnected and fleeting. We imagine a river, rather than a mass of weakly connected water molecules that dance past and disappear. We convince ourselves that memories are real, because if they weren’t, what and who would we be?